For US Healthcare Professionals

About primary hyperoxaluria

Actor portrayal

About primary hyperoxaluria

Primary hyperoxaluria, or PH, is a family of rare genetic disorders causing hepatic oxalate overproduction that can result in progressive kidney damage and failure.1

Primary hyperoxaluria, or PH, is a family of rare genetic disorders causing hepatic oxalate overproduction that can result in progressive kidney damage and failure.1

Hyperoxaluria is a condition defined by increased urinary excretion of oxalate. Oxalate is a metabolic end product that is not naturally broken down. It can also be ingested through food and has no known function in the body.2,3

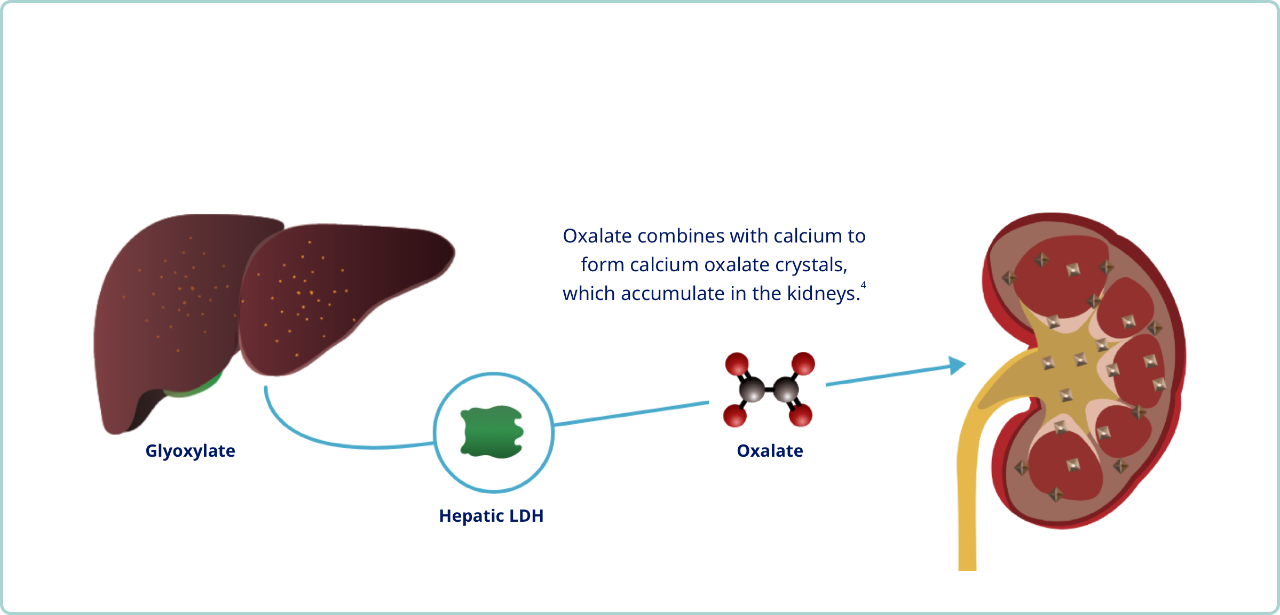

In PH, oxalate is produced by the liver through dysregulation of the glyoxylate metabolic pathway, where hepatic lactate dehydrogenase, or LDH, converts overproduced glyoxylate to oxalate.1,4-6

Oxalate combines with calcium to form calcium oxalate crystals, which accumulate in the kidneys.4

Calcium oxalate crystals combine to form kidney and bladder stones in PH 3

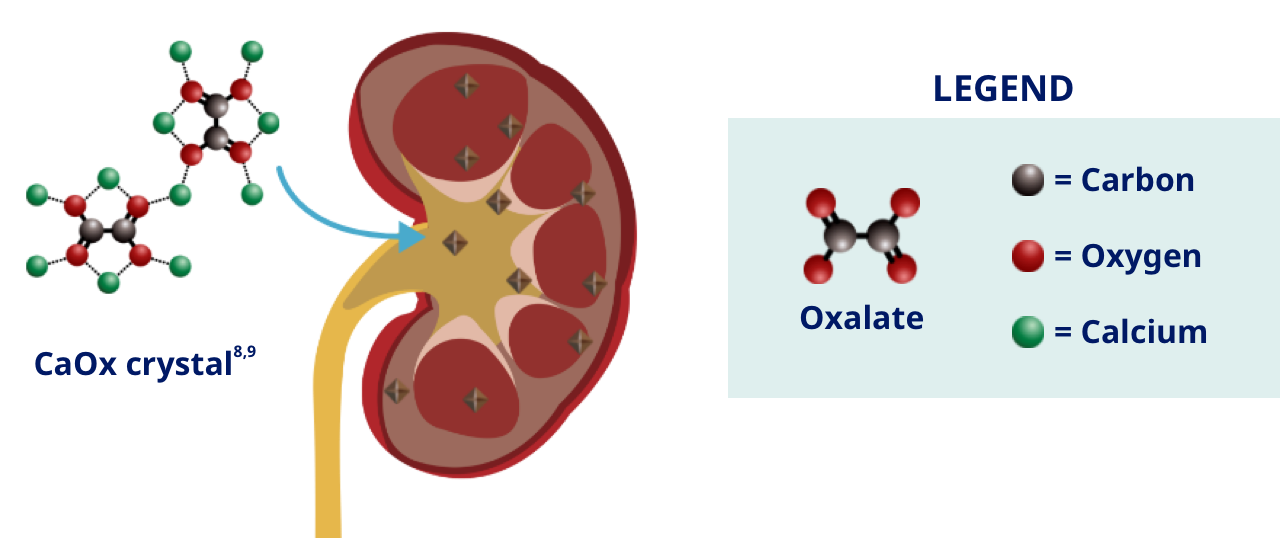

When too much oxalate accumulates in the kidneys, it binds with calcium to form CaOx crystals4,7

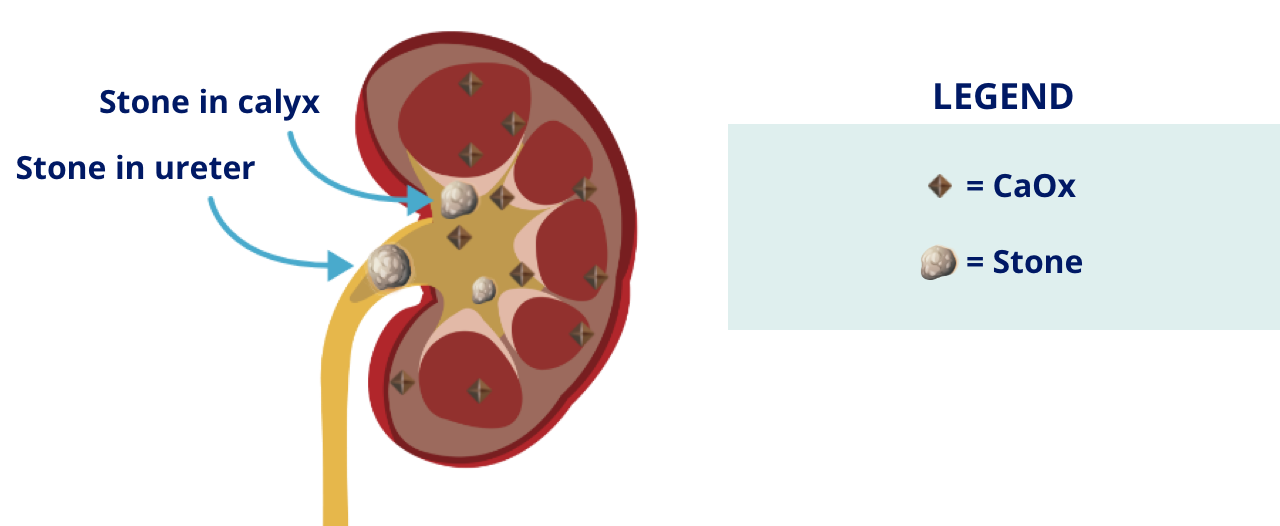

CaOx crystals aggregate to form stones in the kidneys and urinary tract, and also distribute throughout the kidney tissue, causing nephrocalcinosis3

As PH advances, progressive nephrocalcinosis and kidney damage may lead to end-stage kidney disease and systemic oxalosis

Progressive nephrocalcinosis, inflammation, and interstitial fibrosis may lead to end-stage kidney disease (ESKD).4,10

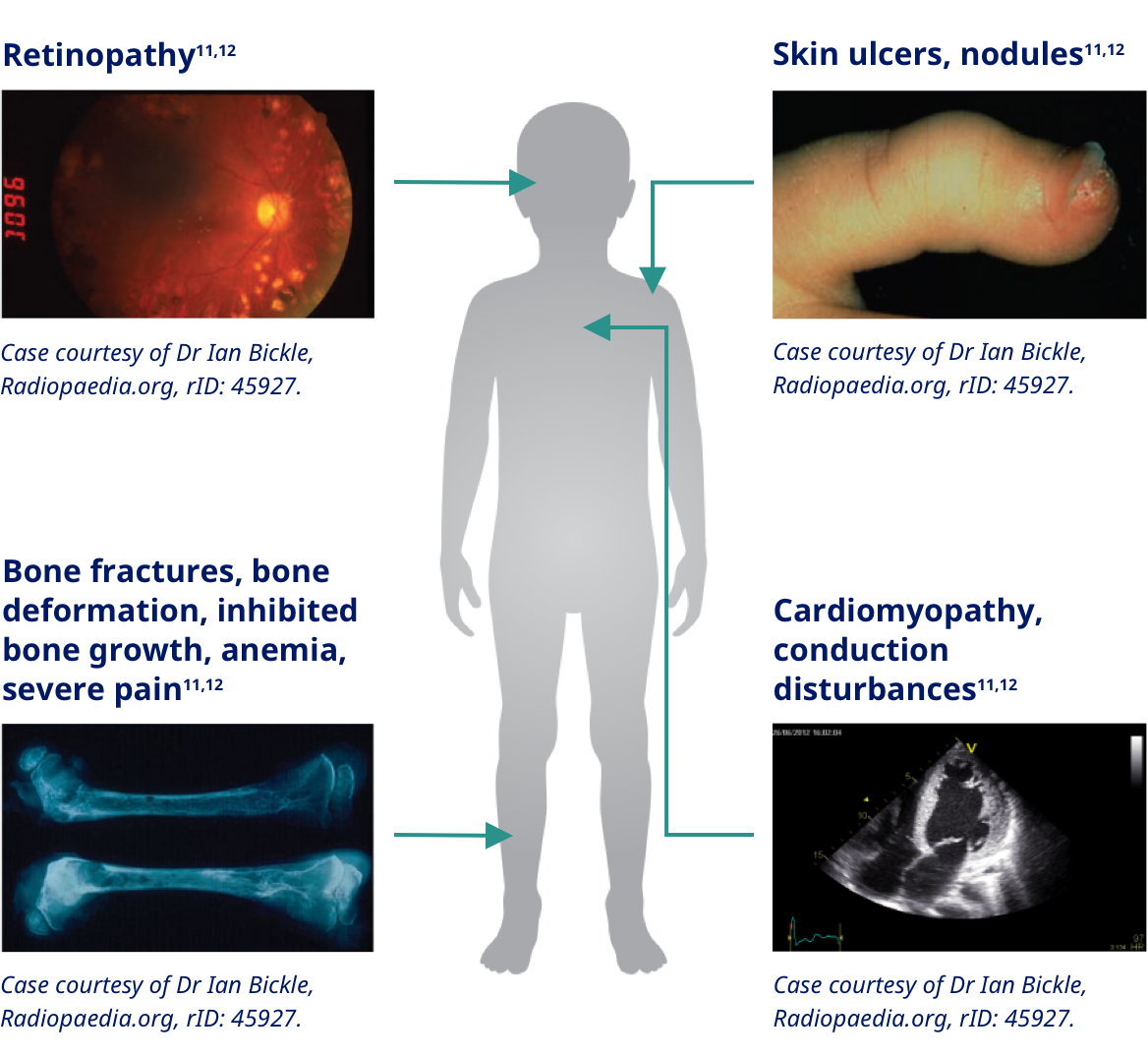

Systemic oxalosis occurs when glomerular filtration rate (GFR) drops below 30 to 45 mL/min and oxalate is no longer adequately filtered by the kidneys. At this point, CaOx crystals begin to deposit in tissues of other organs such as the heart, bone, eyes, and skin.1,10-13

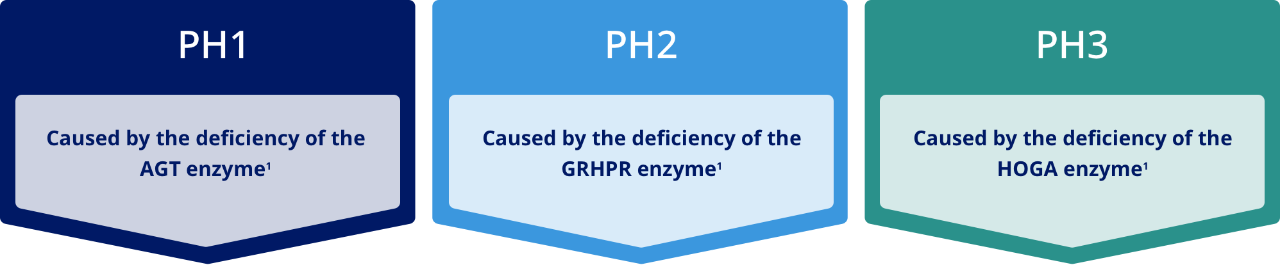

There are 3 known subtypes of primary hyperoxaluria, all of which can cause recurrent kidney stones and progressive kidney damage14-18

There are 3 known subtypes of primary hyperoxaluria, all of which can cause recurrent kidney stones and progressive kidney damage14-18

In each of these subtypes of primary hyperoxaluria, hepatic lactate dehydrogenase, or LDH, catalyzes the conversion of glyoxylate to oxalate, converting this metabolite to a disease-causing agent.4

Abbreviations: AGT, alanine-glyoxylate aminotransferase; GRHPR, glyoxylate reductase-hydroxypyruvate reductase; HOGA, 4-hydroxy-2-oxoglutarate aldolase.

Approximately 11% of patients with signs and symptoms consistent with a diagnosis of PH do not have 1 of the 3 known PH mutations. These patients likely have a PH mutation that has not been discovered yet.14

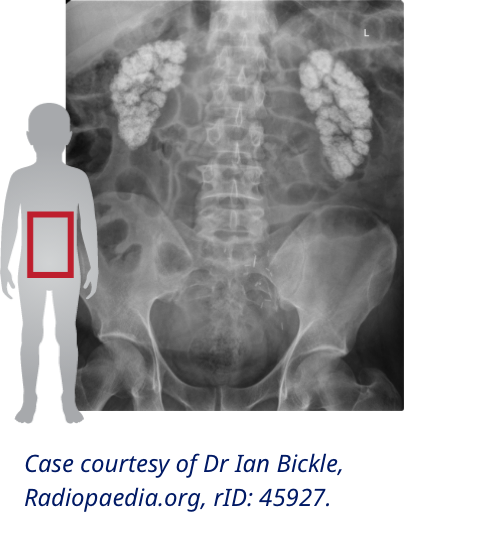

Kidney stones are the hallmark of PH1, PH2, and PH3

Stone burden

- PH1: 73%-100% of patients have stones19,20

- PH2: 83%-100% of patients have stones, many before age 4 years16,21-22

- PH3: Nearly 100% of patients have stones, many before age 4 years17,23-25

PH stone appearance26-28

- Light whitish or pale yellow surface color

- Loose aggregations of different-sized crystals

- Approximately 1.6 cm (0.5 -4.5 cm) in size28

Stone burden

- PH1: 73%-100% of patients have stones19,20

- PH2: 83%-100% of patients have stones, many before age 4 years16,21-22

- PH3: Nearly 100% of patients have stones, many before age 4 years17,23-25

PH stone appearance26-28

- Light whitish or pale yellow surface color

- Loose aggregations of different-sized crystals

- Approximately 1.6 cm (0.5 -4.5 cm) in size28

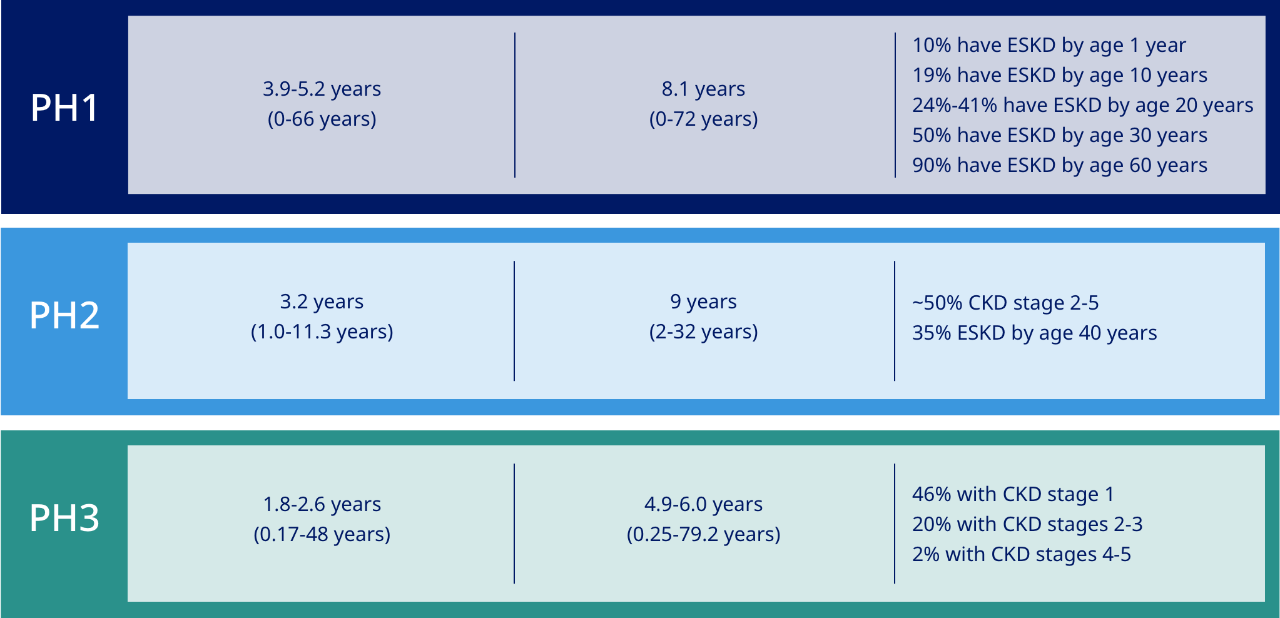

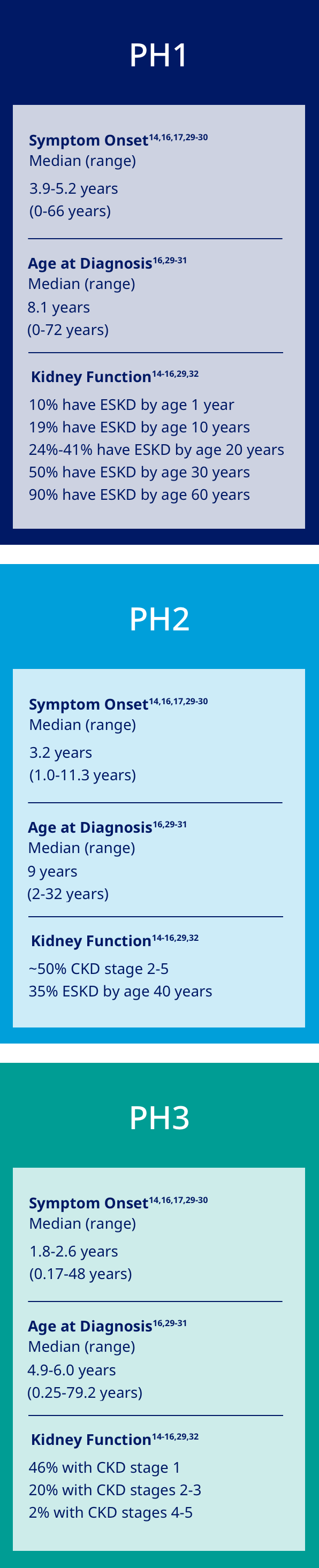

Primary hyperoxaluria often has an early onset, but patients can vary in symptom timing and kidney function

Symptom Onset14,16,17,29-30

Median (range)

Age at Diagnosis16,29-31

Median (range)

Kidney Function14-16,29,32

Patients are often diagnosed years after symptoms begin33

Abbreviations: CKD, chronic kidney disease; ESRD, end-stage renal disease.

Primary hyperoxaluria often has an early onset, but patients can vary in symptom timing and kidney function

Patients are often diagnosed years after symptoms begin33

Abbreviations: CKD, chronic kidney disease; ESRD, end-stage renal disease.

All subtypes of primary hyperoxaluria can have a significant impact on kidney function.14-18

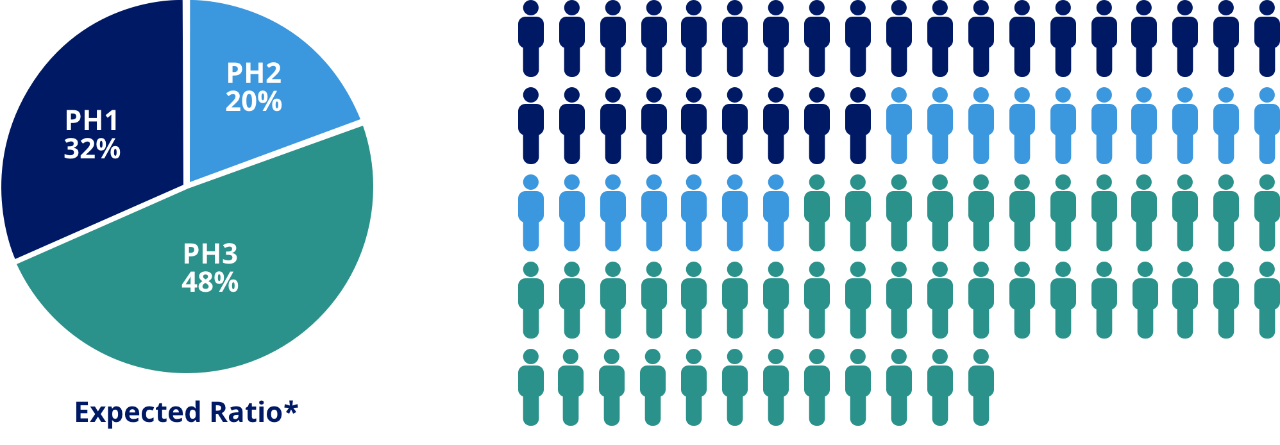

Primary hyperoxaluria is more common than previously thought and significantly underdiagnosed

Primary hyperoxaluria is more common than previously thought and significantly underdiagnosed

Primary hyperoxaluria affects an estimated 8,700 people in the United States.14,34

Estimated US prevalence from clinical studies14,34

<3:1,000,000 or ~1,000 people

Estimated US prevalence from genetic studies14,34

1:38,600 or ~8,700 people

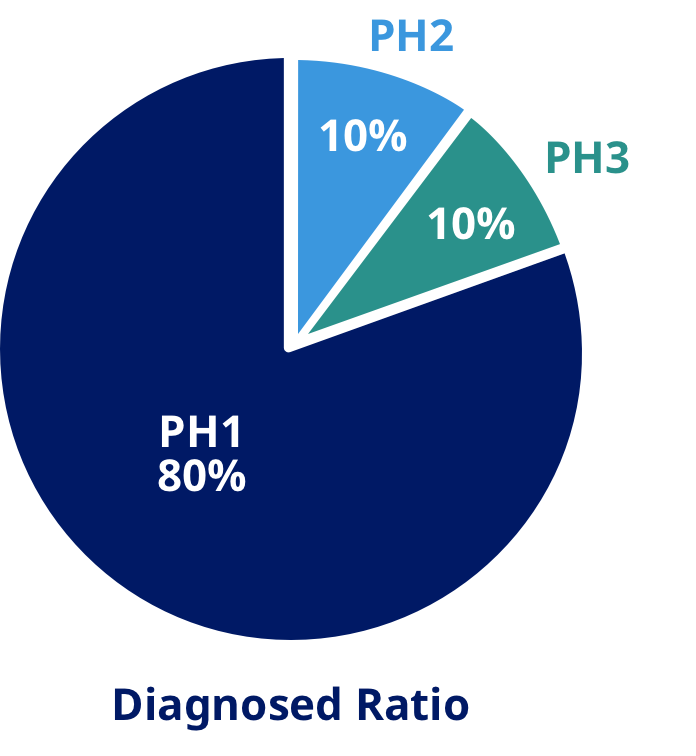

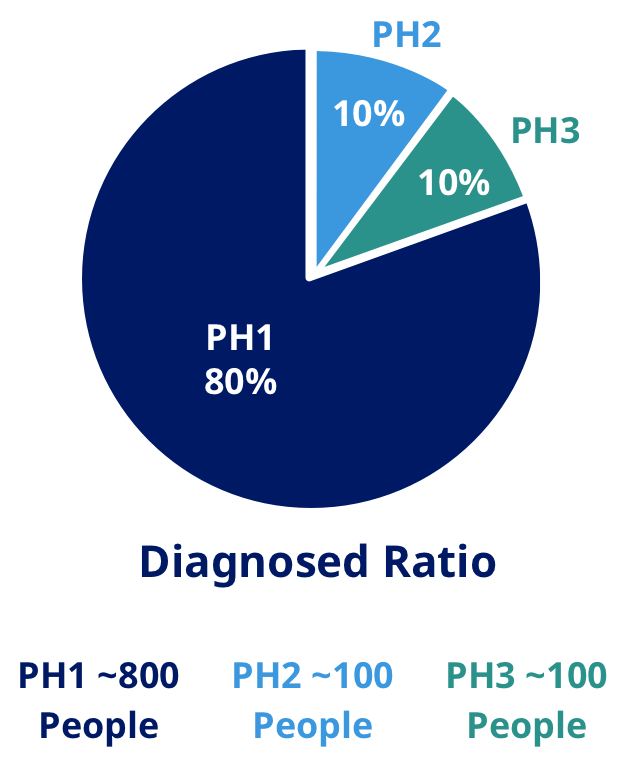

>80% of patients remain undiagnosed14

*Prevalence based on PH mutant alleles found in the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute Exome Sequencing Project (NHLBI ESP) and calculated according to Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium for each PH type using the sum of all alternate PH1, PH2, or PH3 alleles (known and scored as pathogenic) and all wild-type alleles.1

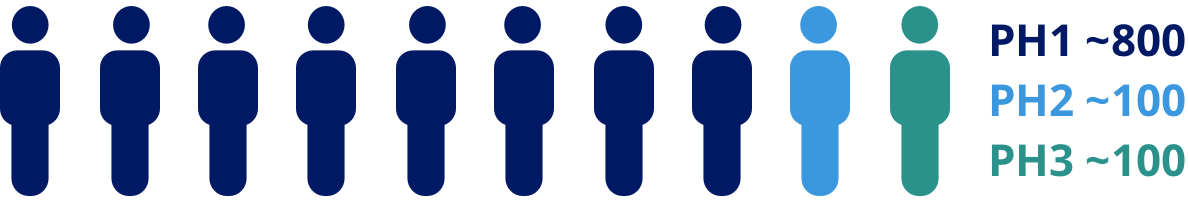

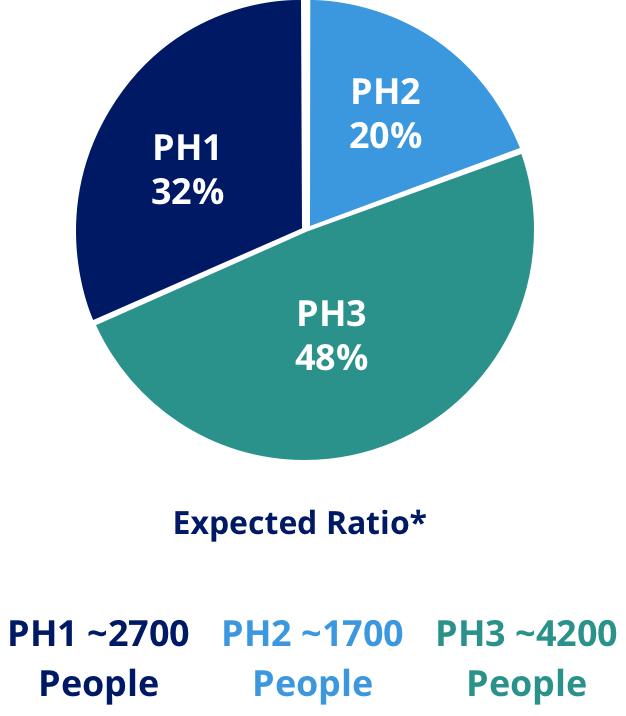

PH1 ~2,700

PH2 ~1,700

PH3 ~4,200

Estimated US prevalence from clinical studies14,34

<3:1,000,000 or ~1,000 people

Estimated US prevalence from genetic studies14, 34

1:38,600 or ~8,700 people

>80% of patients remain undiagnosed14

*Prevalence based on PH mutant alleles found in the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute Exome Sequencing Project (NHLBI ESP) and calculated according to Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium for each PH type using the sum of all alternate PH1, PH2, or PH3 alleles (known and scored as pathogenic) and all wild-type alleles.1

Though PH1 is the most well-known, all PH subtypes are likely undiagnosed.1

Stay informed

Be up to date with the latest news and information about primary hyperoxaluria.

References

- Cochat P, Rumsby G. Primary hyperoxaluria. N Engl J Med. 2013;369(7):649-658.

- Bhasin B et al. Primary and secondary hyperoxaluria: understanding the enigma. World J Nephrol. 2015;4(2):235-244.

- Danpure CJ, Rumsby G. Molecular aetiology of primary hyperoxaluria and its implications for clinical management. Expert Rev Mol Med. 2004;6(1):1-16.

- Lai C et al. Specific inhibition of hepatic lactate dehydrogenase reduces oxalate production in mouse models of primary hyperoxaluria. Mol Ther. 2018;26(8):1983-1995.

- Belostotsky R et al. Primary hyperoxaluria type III—a model for studying perturbations in glyoxylate metabolism. J Mol Med (Berl). 2012;90(12):1497-1504.

- Riedel TJ et al. 4-hydroxy-2-oxoglutarate aldolase inactivity in primary hyperoxaluria type 3 and glyoxylate reductase inhibition. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2012;1822(10):1544-1552.

- Dindo M et al. Molecular basis of primary hyperoxaluria: clues to innovative treatments. Urolithiasis. 2019;47(1):67-78.

- Hochrein O et al. Revealing the crystal structure of anhydrous calcium oxalate, Ca[C2O4], by a combination of atomistic simulation and Rietveld refinement. Z Anorg Allg Chem. 2008;634(11):1826-1829.

- National Center for Biotechnology Information. PubChem Database. Calcium oxalate, CID=33005. Accessed June 11, 2020. https://pubchem.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/compound/33005

- Harambat J et al. Primary hyperoxaluria. Int J Nephrol. 2011;2011:864580.

- Salido E et al. Primary hyperoxalurias: disorders of glyoxylate detoxification. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2012;1822(9):1453-1464.

- Sas DJ et al. Recent advances in the identification and management of inherited hyperoxalurias. Urolithiasis. 2019;47(1):79-89.

- Hoppe B et al. The primary hyperoxalurias. Kidney Int. 2009;75(12):1264-1271.

- Hopp K et al. Phenotype-genotype correlations and estimated carrier frequencies of primary hyperoxaluria. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2015;26(10):2559-2570.

- Harambat J et al. Genotype-phenotype correlation in primary hyperoxaluria type 1: the p.Gly170Arg AGXT mutation is associated with a better outcome. Kidney Int. 2010;77(5):443-449.

- Garrelfs SF et al. Patients with primary hyperoxaluria type 2 have significant morbidity and require careful follow-up. Kidney Int. 2019;96(6):1389-1399.

- Allard L et al. Renal function can be impaired in children with primary hyperoxaluria type 3. Pediatr Nephrol. 2015;30(10):1807-1813.

- Martin-Higueras C, Hoppe B. Chronic kidney disease in patients with primary hyperoxaluria type 3 (PH3) - a meta-analysis from literature. Accepted for oral presentation at: GPN 51st Annual Meeting; 2020.

- Milliner DS et al. Phenotypic expression of primary hyperoxaluria: comparative features of types I and II. Kidney Int. 2001;59(1):31-36.

- Soliman NA et al. Clinical spectrum of primary hyperoxaluria type 1: experience of a tertiary center. Nephrol Ther. 2017;13(3):176-182.

- Takayama T et al. Ethnic differences in GRHPR mutations in patients with primary hyperoxaluria type 2. Clin Genet. 2014;86(4):342-348.

- Johnson SA et al. Primary hyperoxaluria type 2 in children. Pediatr Nephrol. 2002;17(8):597-601.

- Fang X et al. Nine novel HOGA1 gene mutations identified in primary hyperoxaluria type 3 and distinct clinical and biochemical characteristics in Chinese children. Pediatr Nephrol. 2019;34(10):1785-1790.

- Williams EL et al. The enzyme 4-hydroxy-2-oxoglutarate aldolase is deficient in primary hyperoxaluria type 3. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2012;27(8):3191-3195.

- Monico CG et al. Primary hyperoxaluria type III gene HOGA1 (formerly DHDPSL) as a possible risk factor for idiopathic calcium oxalate urolithiasis. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2011;6(9):2289-2295.

- Jacob DE et al. Kidney stones in primary hyperoxaluria: new lessons learnt. PLoS One. 2013;8(8):e70617.

- Daudon M et al. Peculiar morphology of stones in primary hyperoxaluria. N Engl J Med. 2008;359(1):100-102.

- Carrasco A Jr et al. Surgical management of stone disease in patient with primary hyperoxaluria. Urology. 2015;85(3):522-526.

- Mandrile G et al. Data from a large European study indicate that the outcome of primary hyperoxaluria type 1 correlates with the AGXT mutation type. Kidney Int. 2014;86(6):1197-1204.

- Martin-Higueras C et al. Molecular therapy of primary hyperoxaluria. Kidney Int. 2021;100(3):621-635.

- Singh P et al. Clinical characterization of primary hyperoxaluria type 3 in comparison with types 1 and 2. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2022;37(5):869-875.

- Sas DJ, Lieske JC. New insights regarding organ transplantation in primary hyperoxaluria type 1. Kidney Int Rep. 2021;7(2):146-148.

- Hoppe B, Langman C. A United States survey on diagnosis, treatment, and outcome of primary hyperoxaluria. Pediatr Nephrol. 2003;18(10):986-991.

- U.S. Census Bureau population on a date: May 31, 2023. United States Census Bureau website, 2023.