For US Healthcare Professionals

Managing primary hyperoxaluria

Actor portrayal

Managing primary hyperoxaluria

Currently, there is no FDA-approved therapy that addresses all subtypes of primary hyperoxaluria

Currently, there is no FDA-approved therapy that addresses all subtypes of primary hyperoxaluria

Current treatment options fall under 5 categories:

Oxalate reduction

Oxalate reduction

Ribonucleic acid interference (RNAi) therapy1,2

- Two RNAi therapies are approved in PH1 patients

- Works by inhibiting gene expression and selectively reducing hepatic enzymes involved in the overproduction of oxalate associated with PH1

Pyridoxine (vitamin B6)3-8

- One study showed two-thirds of patients with PH1 are completely unresponsive to pyridoxine

- Trial recommended – if no response, discontinue

Dietary changes3

- Avoidance of oxalate-rich foods is recommended

Crystal inhibition

Crystal inhibition

Aggressive hydration3

- Adults/older adolescents: 4 liters water/day

- School-age children: 2-3 liters water/day

- Infants/small children: 1-1.5 liters water/day

- Gastrostomy tube for infants or adults struggling with water intake

Crystallization inhibitors3

- Oral potassium citrate or orthophosphate when glomerular filtration rate (GFR) is well preserved

- Oral sodium citrate for lower GFR rates at risk for hyperkalemia

Kidney stone management3,9

Kidney stone management3,9

- Percutaneous nephrolithotomy (PCNL), or ureteroscopy when PCNL is not indicated

- While PCNL confers the highest “stone-free” rate, it also carries a higher rate of complications and recovery time

- Not recommended: extracorporeal shock wave lithotripsy (ESWL), which can contribute to kidney injury and kidney failure in patients with PH

- Patients with PH overwhelmingly form stones composed of calcium oxalate, which can be resistant to fragmentation by ESWL

- Additionally, patients with PH often have concomitant nephrocalcinosis, which can be misinterpreted in imaging, leading to unnecessary shock wave application to nephrocalcinosis spots instead of stones

Renal replacement therapy

Renal replacement therapy

- Intermittent hemodialysis (HD), as often as 6 days/week, with additional peritoneal dialysis (PD) in some patients3

- Recommended for patients with plasma oxalate levels >30-45 μmol/L3

- Dialysis is not able to sufficiently remove all endogenously overproduced oxalate. Even in patients receiving a combination of daily HD and PD, a weekly elimination of less than half of endogenously produced oxalate can be achieved10

- Often serves as a temporary therapy; the goal is to keep plasma oxalate levels below plasma calcium oxalate supersaturation (30-45 μmol/L) to prevent systemic oxalosis in patients awaiting organ transplant3,11,12

Organ transplant

Organ transplant

- Simultaneous liver-kidney transplant recommended at chronic kidney disease (CKD) stage 3b3

- 34% to 46% of patients with PH1 and 11% of patients with PH2 may require an organ transplant5,8,13

- 23% to 36% of transplanted organs may fail within 5 years of transplant14

- Kidney and liver transplant recipients require lifelong immunosuppression15

Most patients with PH live with recurring kidney stones that can lead to progressive kidney failure16,17

Most patients with PH live with recurring kidney stones that can lead to progressive kidney failure16,17

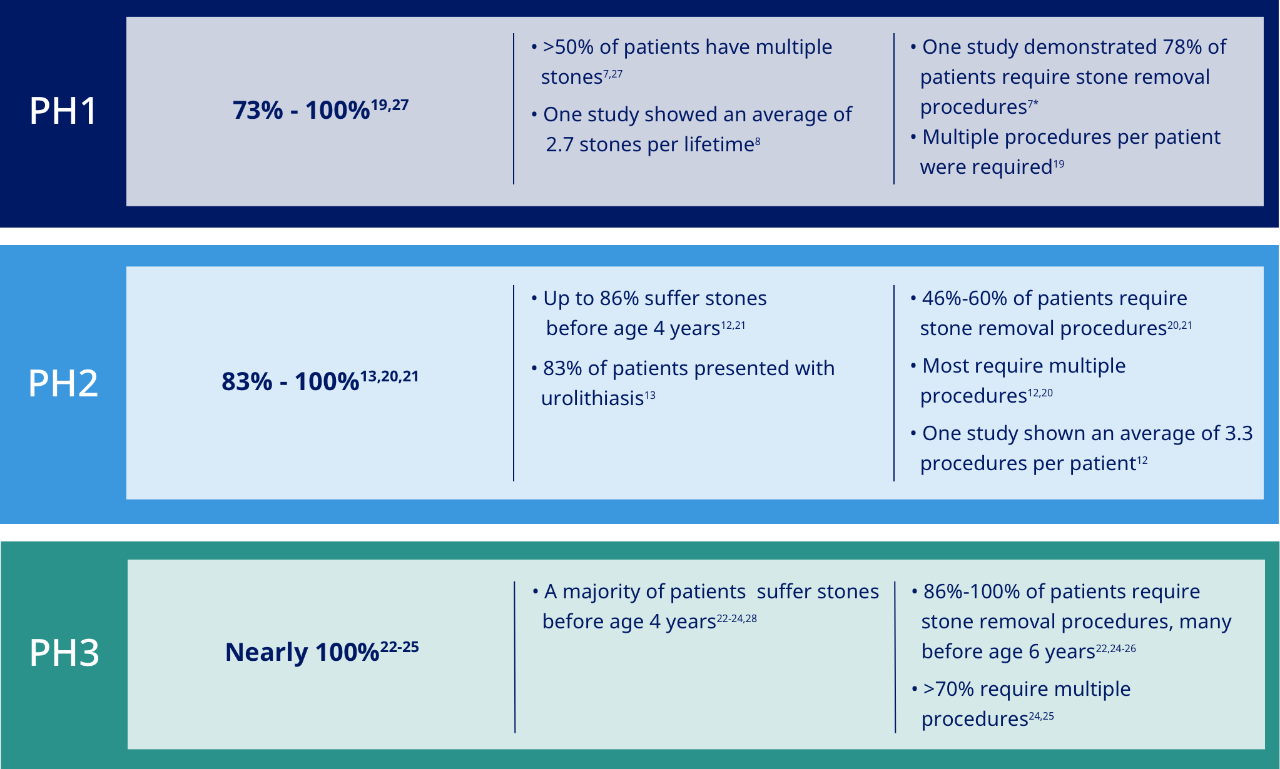

All subtypes of primary hyperoxaluria are linked to kidney stones and burdensome stone removal procedures.8,13,18-26

70% of patients with PH require one or more urologic procedures during their lifetime18

*Invasive stone removal posed a great burden to patients, including potential adverse effects such as bleeding, scarring, infections, and internal organ damage, as well as days in inpatient care.7

% of Patients with stones

Stone burden

Stone removal

The burden of many current treatments is high. Hyperhydration can have a significant impact on a patient’s quality of life, causing interruptions at school, work, and social events, as well as a loss of sleep. An unlimited bathroom pass can help children take more frequent breaks at school.3,16,29

Adults & older adolescents3

135 ounces, 4 liters, or 17 cups of water/day

School-age children3

68-101 ounces, 2-3 liters, or 8-13 cups of water/day

Infants/small children3

34-51 ounces, 1-1.5 liters, or 4-6.5 cups of water/day

Infants and others struggling with water intake may require a gastrostomy tube (G-tube)3

Primary hyperoxaluria creates significant burden for patients and caregivers as they try to manage their disease; despite their efforts, most remain fearful of developing stones and continued kidney damage. A survey showed that 94% of patients hope for new therapies that would prevent dialysis, organ transplant, and oxalosis, and/or improve chances of a normal life span.16,19

53% of patients with PH and 36% of caregivers are concerned about kidney stones, procedures, and therapies16

65% of patients with PH and 24% of caregivers are worried about kidney failure16

71% of patients with PH and 52% of caregivers are fearful of organ transplant16

Stay informed

Be up to date with the latest news and information about primary hyperoxaluria.

References

- OXLUMO [package insert]. Cambridge, MA: Alnylam Pharmaceuticals Inc; 2020.

- Forbes FA, Brown BD, Lai C. Therapeutic RNA interference: a novel approach to the treatment of primary hyperoxaluria. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2022;88:2525–2538.

- Sas DJ et al. Recent advances in the identification and management of inherited hyperoxalurias. Urolithiasis. 2019;47(1):79-89.

- Hopp K et al. Phenotype-genotype correlations and estimated carrier frequencies of primary hyperoxaluria. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2015;26(10):2559-2570.

- Harambat J et al. Genotype–phenotype correlation in primary hyperoxaluria type 1: the p.Gly170Arg AGXT mutation is associated with a better outcome. Kidney Int. 2010;77(5):443-449.

- Mandrile G et al. Data from a large European study indicate that the outcome of primary hyperoxaluria type 1 correlates with the AGXT mutation type. Kidney Int. 2014;86(6):1197-1204.

- van Woerden CS et al. Clinical implications of mutation analysis in primary hyperoxaluria type 1. Kidney Int. 2004;66(2):746-752.

- Danese D et al. Understanding the burden of primary hyperoxaluria type 1 (PH1): a survey of physician experiences with PH1. Poster presented at: IPNA 18th Congress; October 17-21, 2019; Venice, Italy.

- Carrasco A Jr et al. Surgical management of stone disease in patient with primary hyperoxaluria. Urology. 2015;85(3):522-526.

- Hoppe B. A United States survey on diagnosis, treatment, and outcome of primary hyperoxaluria. Nat Rev Nephrol. 2012;8(8):467-475.

- Harambat J et al. Characteristics and outcomes of children with primary oxalosis requiring renal replacement therapy. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2012;7(3):458-465.

- Cochat P et al. Primary hyperoxaluria Type 1: indications for screening and guidance for diagnosis and treatment. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2012;27(5):1729-1736.

- Garrelfs SF et al. Patients with primary hyperoxaluria type 2 have significant morbidity and require careful follow-up. Kidney Int. 2019;96(6):1389-1399.

- Bergstralh EJ et al. Transplantation outcomes in primary yperoxaluria. Am J Transplant. 2010;10(11):2493-2501.

- Neuberger JM et al. Practical recommendations for long-term management of modifiable risks in kidney and liver transplant recipients: a guidance report and clinical checklist by the consensus on managing modifiable risk in transplantation (COMMIT) group. Transplantation. 2017;101(4S)(suppl 2):S1‐S56.

- Lawrence JE, Wattenberg DJ. Primary hyperoxaluria: the patient and caregiver perspective. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2020;15(7):909-911.

- Milliner DS et al. Endpoints for clinical trials in primary hyperoxaluria. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2020;15(7):1056-1065.

- Tang X et al. Nephrocalcinosis is a risk factor for kidney failure in primary hyperoxaluria. Kidney Int. 2015;87(3):623-631.

- Milliner DS et al. Phenotypic expression of primary hyperoxaluria: comparative features of types I and II. Kidney Int. 2001;59(1):31-36.

- Takayama T et al. Ethnic differences in GRHPR mutations in patients with primary hyperoxaluria type 2. Clin Genet. 2014;86(4):342-348.

- Johnson SA et al. Primary hyperoxaluria type 2 in children. Pediatr Nephrol. 2002;17(8):597-601.

- Fang X et al. Nine novel HOGA1 gene mutations identified in primary hyperoxaluria type 3 and distinct clinical and biochemical characteristics in Chinese children. Pediatr Nephrol. 2019;34(10):1785-1790.

- Williams EL et al. The enzyme 4-hydroxy-2-oxoglutarate aldolase is deficient in primary hyperoxaluria type 3. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2012;27(8):3191-3195.

- Allard L et al. Pediatr Nephrol. 2015;30(10):1807-1813.

- Monico CG et al. Primary hyperoxaluria type III gene HOGA1 (formerly DHDPSL) as a possible risk factor for idiopathic calcium oxalate urolithiasis. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2011;6(9):2289-2295.

- Wang W et al. Mutation hot spot region in the HOGA1 gene associated with primary hyperoxaluria type 3 in the Chinese population. Kidney Blood Press Res. 2019;44(4):743-753.

- Soliman NA et al. Clinical spectrum of primary hyperoxaluria type 1: experience of a tertiary center. Nephrol Ther. 2017;13(3):176-182.

- Belostotsky R et al. Mutations in DHDPSL are responsible for primary hyperoxaluria type III. Am J Hum Genet. 2010;87(3):392-399.

- Jackson EC, Avendt-Reeber M. Urolithiasis in children—treatment and prevention. Curr Treat Options Pediatr. 2016;2(1):10-22.

- Lai C et al. Specific inhibition of hepatic lactate dehydrogenase reduces oxalate production in mouse models of primary hyperoxaluria. Mol Ther. 2018;26(8):1983-1995.

- Setten RL et al. The current state and future directions of RNAi-based therapeutics. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2019;18(6):421-446.

- Dicerna provides initial observations from PHYOX™3 trial of nedosiran for treatment of primary hyperoxaluria and an update on data presentation plan. News release. Dicerna Pharmaceuticals Inc; March 31, 2020. Accessed August 3, 2023. https://www.biospace.com/article/releases/dicerna-provides-initial-observations-from-phyox-3-trial-of-nedosiran-for-treatment-of-primary-hyperoxaluria-and-an-update-on-data-presentation-plan.

- Martin-Higueras C et al. Molecular therapy of primary hyperoxaluria. J Inherit Metab Dis. 2017;40(4):481-489.